Legislation concerning sex work is not new by any means. The oldest intact legal document, the Code of Hammurabi, describes legal regulations about sex work in ancient Babylon, but regardless of the intent of the law or an individual or societal attitude towards sex work, there is more to consider than just whether a person can pay for sex. Women pay the price for a lack of forethought in sex work legislation, as in the case of the White Slave Trafficking Act and the Chamberlain-Kahn Act. Both of these acts had a profound impact not only on sex work at large, but also on our very own community in Fort Smith.

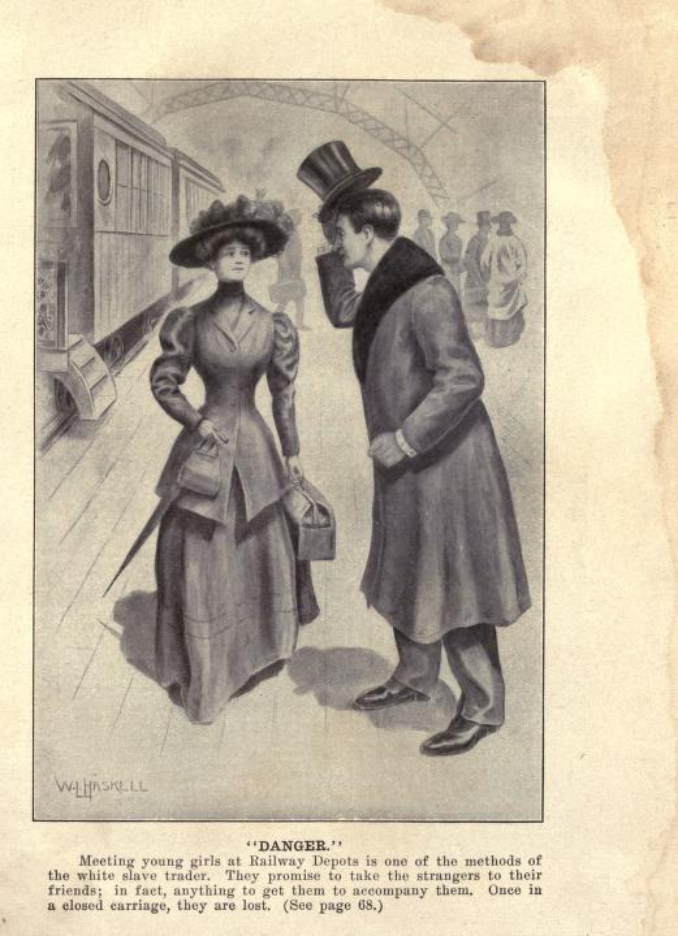

Photo from War on the White Slave Trade by Ernest Bell

In 1910, the panic induced by the so-called “white slave” trade made way for the White Slave Traffic Act, more commonly known as the Mann Act. The purpose behind the act was to bring justice to women who had been forced into a life of sex work. Unfortunately, the vague language therein allowed for broad interpretation. The act originally stated that no one could transport “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose…” This vague language put the terms of morality in the hands of whoever was doing the arresting, which meant much of the time, women were “rescued” from situations that were consensual. In fact, if a woman did consent, as in the case of Gebardi et al. V. United States, she could be indicted as well with a conspiracy charge. This, of course, affected prostitutes quite a bit. Formerly, prostitutes might be charged and fined for a misdemeanor like disturbing the peace or some kind of indecent conduct charge. Conspiracy under the Mann Act, however, was a felony, and had much farther-reaching effects on a woman’s livelihood.

The Mann Act is still in effect today, though it has been reworked to reduce improper use. Among other changes, “debauchery” and “other immoral purpose” are no longer in the wording at all. Instead, according to the Office of the Law Revision Council, it states: “Whoever knowingly transports any individual in interstate or foreign commerce, or in any Territory or Possession of the United States, with intent that such individual engage in prostitution, or in any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense, or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both.” In recent years such notable people as R. Kelly and P. Diddy have been prosecuted under the Mann Act for sexual crimes, which much better represent the spirit by which the law was originally drafted.

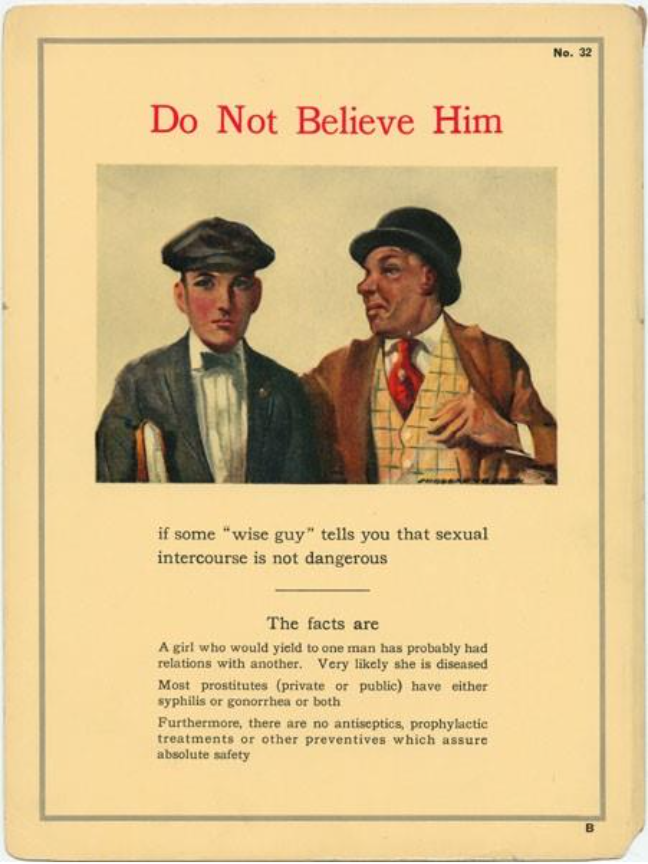

About 8 years after the introduction of the Mann Act came the introduction of the Chamberlain-Kahn Act. During World War I, soldiers were contracting venereal disease at rates too quick to be treated, and in 1918 when the United States entered the first world war, the increase of venereal disease in the military men necessitated some kind of intervention. The Chamberlain-Kahn act was enacted just over a year after the United States entered the war, and prohibited prostitutes from being “within such reasonable distance of any military camp, station, fort, post, cantonment, training or mobilization place as the Secretary of War shall determine…” More concerningly, it also allowed people (usually women) suspected of having venereal disease to be detained, tested for venereal disease, and quarantined without their consent. Those found to have a venereal disease were often sentenced to public health institutions until they were cured, subjected to painful treatments, and required to attend structured activities often including forced labor. In his paper The Long American Plan: The U.S. Government’s Campaign Against Venereal Disease and its Carriers, Scott Stern describes some of these horrific conditions. One Fort Smith woman, Betty Adams, was sentenced to a detention hospital in 1936 and brought her case to a judge on the basis of deprivation of her liberties.

Of course, women who were prostitutes were targeted with zeal, making them even more vulnerable than did whatever circumstance led to their employment as a sex worker.

Photo from the Venereal Disease Visual Archive

By the 1940s, the American Plan was no longer a talking point as far as public health was concerned, but venereal disease was still a great concern. In Fort Smith, it was still common practice to send women suffering from venereal disease to detention hospitals- the nearest being in Hot Springs, AR. In an article in the Southwest American from 1941, Dr. Johnson, a venereal disease specialist, comments on the lack of federal funds, which kept health officials from transporting women to such facilities for treatment. It was also common practice to send women suffering from venereal disease back to their homes if they were in Fort Smith just to visit. Though prostitutes were targeted in particular, legal prostitution in fort smith ended in 1924. Because of this, Miss Laura’s (or, as it was known at the time, Bertha’s Place) was likely not targeted as much as the women selling on the streets. The general public was not aware that Bertha’s Place was open for business as late at 1948, as is evidenced by the comment from Dr. John Porterfield, a visiting venereal disease control officer, in 1946 who stated “I understand, however, from undercover reports in Fort Smith, that prostitution is not a big problem here.”

This does not mean that the women employed at Bertha’s Place were safe, though. Reasons a woman might be suspected of prostitution or disease were largely arbitrary. Stern discusses in his book talk for The Trials of Nina McCall that women were often detained for things as inconsequential as going out with a gentleman unchaperoned, being a waitress, dining alone, or even enjoying a conversation with a serviceman too much. Stern also found it worth mentioning that the false positive rate for venereal disease testing was around 40% at the time.

Fortunately, the Chamberlain-Kahn Act is no longer in effect, but many laws in local communities that were inspired by the American Plan are still on the books today, as Stern discusses in The Long American Plan. As recently as the 1970s, women were forcibly detained, tested, and treated for venereal disease, and the American Plan most likely influenced the social and governmental response to the AIDS crisis in the 80s and 90s.

Both the Mann Act and the Chamberlain-Kahn Act were meant to protect women, public health, and positively affect social hygiene, but vague wording and the granting of power without proper oversight and procedure lead to women being harmed more than if nothing had been done at all. Our very own Fort Smith community was deeply affected by this legislation due to our long history of prostitution and connection with the military base at Fort Chaffee. These acts made a vulnerable class of women even more vulnerable by affecting their livelihood without offering a viable alternative and causing emotional and physical damage when women were subjected to forcible treatment in public health facilities. Finally, these acts left an impression on legislation at both the local and federal level that, for better or worse, affect responses to sex trafficking and public health to this day.

Sources if the links are lost

The mann act full text (original) https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/unforgivable-blackness/mann-act-full-text/

Mann Act implications/overview https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/mann_act

Current Mann Act wording https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title18/part1/chapter117&edition=prelim

Gebardi vs US https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/287/112

P Diddy court transcript https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/media/1368556/dl

R Kelly court trascript https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndil/press-release/file/1182181/dl

Chamberlain Kahn Act https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/40/STATUTE-40-Pg845.pdf

Book talk trials of nina mccall https://www.c-span.org/program/book-tv/the-trials-of-nina-mccall/503325

FS woman detained to be sent to hot springs

Code of Hammurabi https://avalon.law.yale.edu/ancient/hamframe.asp

Do not believe him picture https://vdarchive.newmedialab.cuny.edu/items/show/382

Danger photo https://archive.org/details/fightingtraffici00bell/fightingtraffici00bell/page/184/mode/2up